Leonard Rowles hopes to one day use his love for graphic design and art to get a job as an architect. The 22-year-old is currently living in a group home in Carson, California after living for two years in a secured setting at Porterville Developmental Center (PDC) from 2020 to 2022.

Rowles, who has autism, was arrested in March 2020 after a disagreement with his stepfather. He was charged with great bodily harm and vandalism and was sent to PDC. He was briefly released but then rearrested. While in jail he was referred to YAI’s intensive individualized transition services (IITS), a collaborative initiative with the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) and Regional Centers throughout the state of California.

According to the CDC, people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) are disproportionately represented in the prison population. Nearly one in four prisoners have a cognitive disability. Diagnoses such as autism, fetal alcohol syndrome, ADD/ADHD, Down syndrome, and general cognitive impairment are common in the criminal justice system.

IITS provides clinical case management for adults with I/DD, complex behavioral needs, substance use, and/or involvement with the justice system who all require intense intervention by a specialist team. YAI is the only IITS provider in California providing this crucial service for people with a high risk of being incarcerated again.

A key for IITS to be successful is to start supporting the person before they leave PDC to facilitate the transition. According to Sharon Cyrus-Savary, Clinical Director of IITS, starting this support 60-90 days before a person is released can make a huge difference. In most instances, IITS is called when the person is already having problems after being released.

“We want to meet the person at PDC so they understand what we do because a lot of people we support have executive function challenges that include impulsivity, emotion dysregulations, and inflexible thinking, among other challenges – the more we can provide comprehensive assessments and linkages in the community and they get used to the team, the less challenges they will experience when they transition out into the community,” she said.

In Rowles’ case, YAI worked with him and his support team to facilitate his transition from PDC to a respite home in November 2022 where the IITS team had weekly check-ins with him for three months. Today, Rowles continues to receive additional IITS supports at his current home, where he has lived since February. People are usually in the program for 18 months with a possibility of extension if their care team decides it’s needed.

“People receiving IITS are so misunderstood and there are so many stereotypes and preconceptions of who they are. We are here to walk them through it so that the outside world can better understand them. We set them up with the training they need,” said LaShawna Hughes, a IITS Transition Coordinator who has been working with Rowles since March of this year.

IITS looks at the challenges a person is facing in the context of their life and relationships. The team provides intensive, individualized services, including performing evidence-based comprehensive risk assessments, developing trauma-informed person-centered plans, and making recommendations regarding nursing, medical, and psychiatric services.

For Rowles, IITS has focused on finding techniques to help him deal with the feelings of frustration that often arise in his group home – an environment he finds restrictive. His support team is working to understand his triggers and what can be done to help him deescalate those emotions.

“Sometimes the staff say things that upset me, and I break things,” said Rowles. “I try to have a conversation about asking for something, but they deny me, and I get upset when I am trying to explain myself... then when the conversation escalates, they call the police.”

To help mediate, Hughes provides crisis intervention to the staff at Leonard’s home too, so they can better support him.

“So far, Leonard’s been able to manage his feelings well using some of the problem-solving techniques we have been working on,” said Hughes. “Society tends to write off people like Leonard because they are unaware of the individual’s capabilities and don’t see they have so much in them but just need the additional help to get there.”

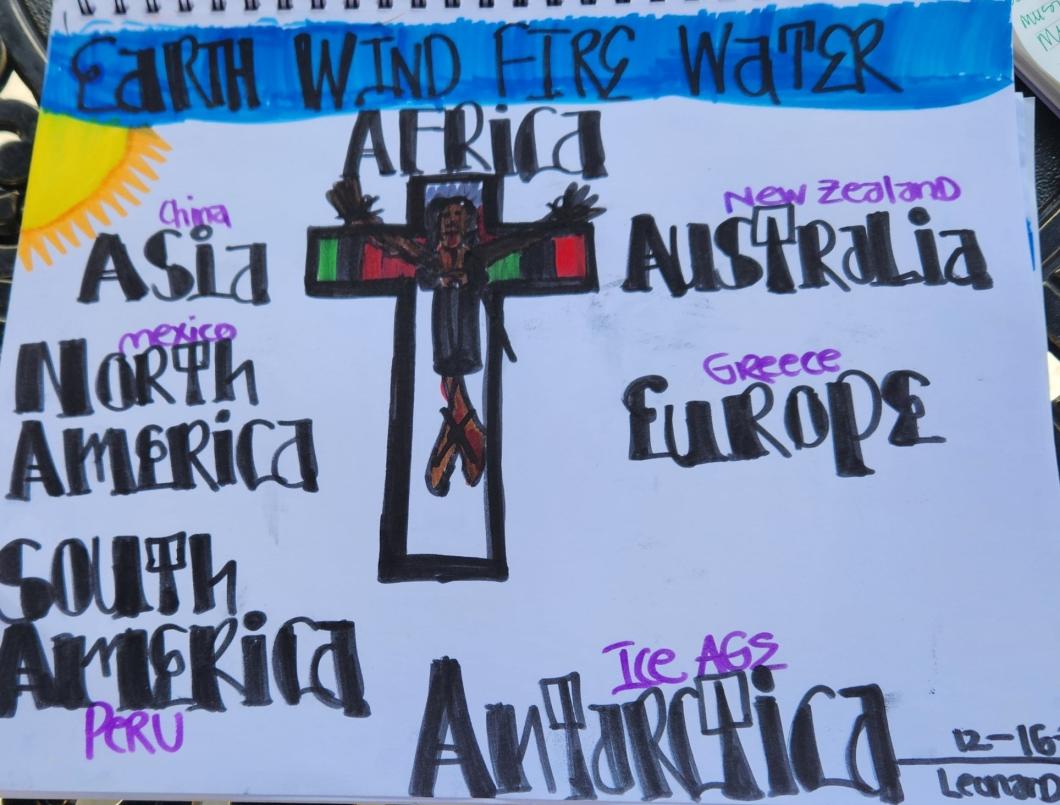

The end goal for many is to be able to live as independently as possible. For Rowles, that means going back to school to earn his degree in architecture and achieving everyday milestones like getting a driver’s license, starting a family, and using his artistic talent to pursue a career in design.

“People judge you in a negative way because you came out of jail and it can be a lonely experience,” said Rowles. “I don’t pay attention when people judge me...I want to try to move forward with my life and have a positive outlook.”